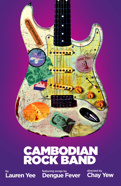

How Playwright Lauren Yee Took the Khmer Rouge Genocide and Turned It Into the Joyful Cambodian Rock Band

(Photos by Emilio Madrid for Broadway.com)

When actor Joe Ngo was growing up, his parents would tell him stories about their time as labor camp prisoners under the Khmer Rouge regime. One story stuck with him. It was about the time that his mother witnessed a prison guard killing a young boy for stealing fruit. “He literally takes a machete and cuts this kid open, takes out his gallbladder and eats it in front of people,” Ngo retells with a grimace. “My mom said it was the most horrific thing she's ever seen.” His mother was then told to dig a grave for that boy.

Horror stories like that about the Cambodian genocide, which murdered approximately two million people from 1975 to 1979, are pretty standard (especially if you saw the 1985 Oscar-nominated film, The Killing Fields). But what is rarely told is how people like Ngo’s parents endured those traumatic experiences and reclaimed their humanity after. That story of survival is what Ngo is currently telling every night in Cambodian Rock Band by Lauren Yee, at off-Broadway’s Signature Theatre until March 15. It's the first work in Yee's Signature Theatre residency.

Cambodian Rock Band moves back and forth in time between the ’70s and 2008. In the modern day, a Cambodian-American named Neary (played by Courtney Reed) goes to Cambodia to prosecute a Khmer Rouge official. In the process, she also finds out more about her father, Chum, who is a survivor but has never talked about his story. The play then flashes back to 1975 when Chum had a rock band (hence the name of the play).

Ngo plays Chum and to him, the play is “between a father and a daughter: a father who has secrets that he's keeping, and a daughter who is trying to make sense of who she is in the world through her father's pain.” Ngo is the only Cambodian actor in the cast and helped Yee develop the play (he’s also played Chum in three previous productions of Cambodian Rock Band, which has become something of a sensation in regional theaters).

When Yee met Ngo met in 2013, she had already started working on the play, but wasn't happy with the drafts. “They kept being plays about victims, which was not something I was very excited by,” Yee explains. Meeting Ngo and hearing him tell his family’s stories was the key to unlocking the work: “The big revelation with Joe was that joy can be a survival strategy. People who go through traumatic things deal with them in a lot of different ways, and it was a different take on what a surviver might look and sound like.”

While developing the role of Chum with Yee, Ngo was inspired by his own parents. “When I look at my mom and see how joyful she is, I can tell it literally comes from the fact that she is a survivor and she's grateful for the life that she has,” he says. “She jokes with people all the time, she's ebullient, she's just full of life! That's Chum for me. When I created the character, he has my dad's mannerisms and he has my mom's joy.”

During the Khmer Rouge-orchestrated genocide, around 90 percent of Cambodia’s artist population were systematically murdered. So in creating a play about that time, Yee wanted to show the vibrancy of the country's culture, so audiences can understand the tragedy of what was lost. That’s where the music comes in. The play action is broken up by songs sung by the cast. Yee sourced the songs from a Cambodian-American band called Dengue Fever and also Cambodian oldies from the 1960s and ’70s, when the country was influenced by Western pop-rock. While the lyrics are in Khmer, the music stylings will sound familiar to anyone who is a fan of surf and psychedelic rock. The entire show is performed by a cast of just six Asian-American actors who all act, sing and play their own musical instruments. When asked about what it’s like to play his own personal guitar during the show, Ngo just laughs, saying, “I've been playing since I was 13-14. I was never that good, I just happened to get good for this show.”

So it’s part dramatic play, part rock concert, and Yee promises it all comes together: “If Cambodian Rock Band is about an oppressive regime that's trying to wipe music and musicians off the face of the Earth, the most revolutionary thing you can do is show that music.”

While Cambodian Rock Band discusses tragedy, it’s not about victims; it’s about survival and resilience, and how music can be a way to overcome trauma, heal wounds and connect generations. Which, according to Ngo, is very true to life. “Cambodian people have this ability to dance, and sing and laugh and celebrate life because of how difficult and hard that time was,” explains Ngo, who grew up in Monterey Park, California, near a thriving Cambodian music scene.

Since she isn’t Cambodian (she’s Chinese-American), Yee wanted to make sure there were plenty of Khmer voices involved in the creation of the play. That’s why she used Ngo and his parents as sources, and Dengue Fever even came in and taught the actors how to properly play their music. Yee offers the following tips for creators who want to write outside of their lived experiences: “Does it center on the people it's supposed to be about? Do they get to be the heroes of their own story? Are they fully-fleshed-out human beings that the audience can sympathize and identify with on a personal level? Are they compelling and complex? If someone from this community saw this show, is it centered around the things they might be interested in?” she posits. “Those are the questions you should ask yourself.”